Calculus

How To Find Relative Extrema [Calculus 101]

Learn the definition of relative extrema, how to identify points of relative minima and maxima, and practice your knowledge with worked examples.

Rachel McLean

Subject Matter Expert

Calculus

08.11.2023 • 6 min read

Subject Matter Expert

Learn about Rolle's Theorem conditions, Lagrange’s Mean Value Theorem, and differentiable and continuous functions. We’ll also practice with solved examples.

In This Article

Rolle’s Theorem is one of the most critical theorems in calculus. Named after the French mathematician Michel Rolle, this theorem is a special case of Lagrange’s Mean Value Theorem.

Rolle’s Theorem goes like this:

Let the function be differentiable on the open interval and continuous on the closed interval . If , then at least 1 point is in the interval where .

In other words, Rolle’s Theorem states that if your function has 2 points and with the same y-value, then there must be at least 1 relative minimum or maximum between these 2 points where the function "turns around." The first derivative is 0 at this point.

Remember, this theorem only holds true as long as your function is also differentiable on and continuous on .

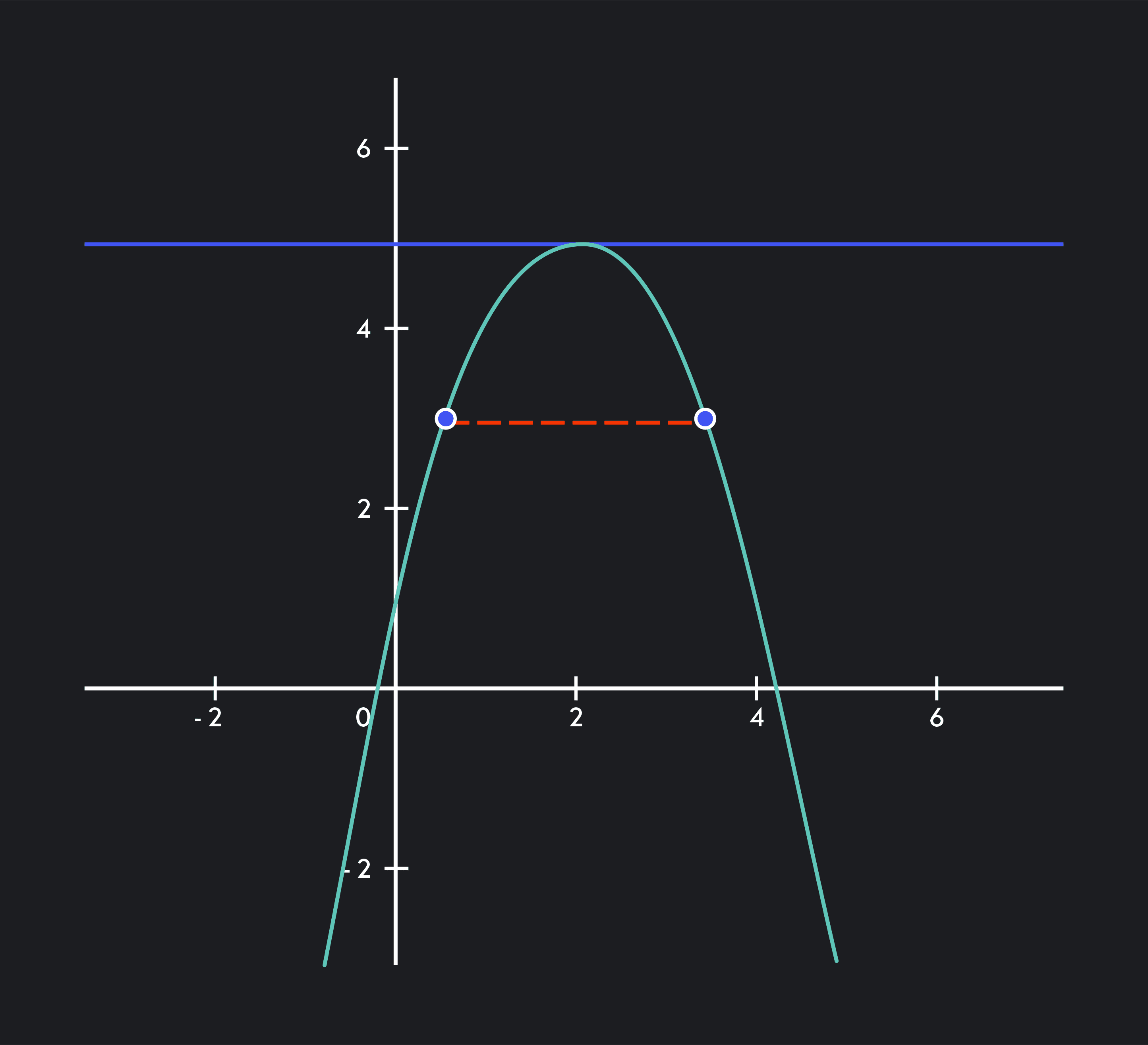

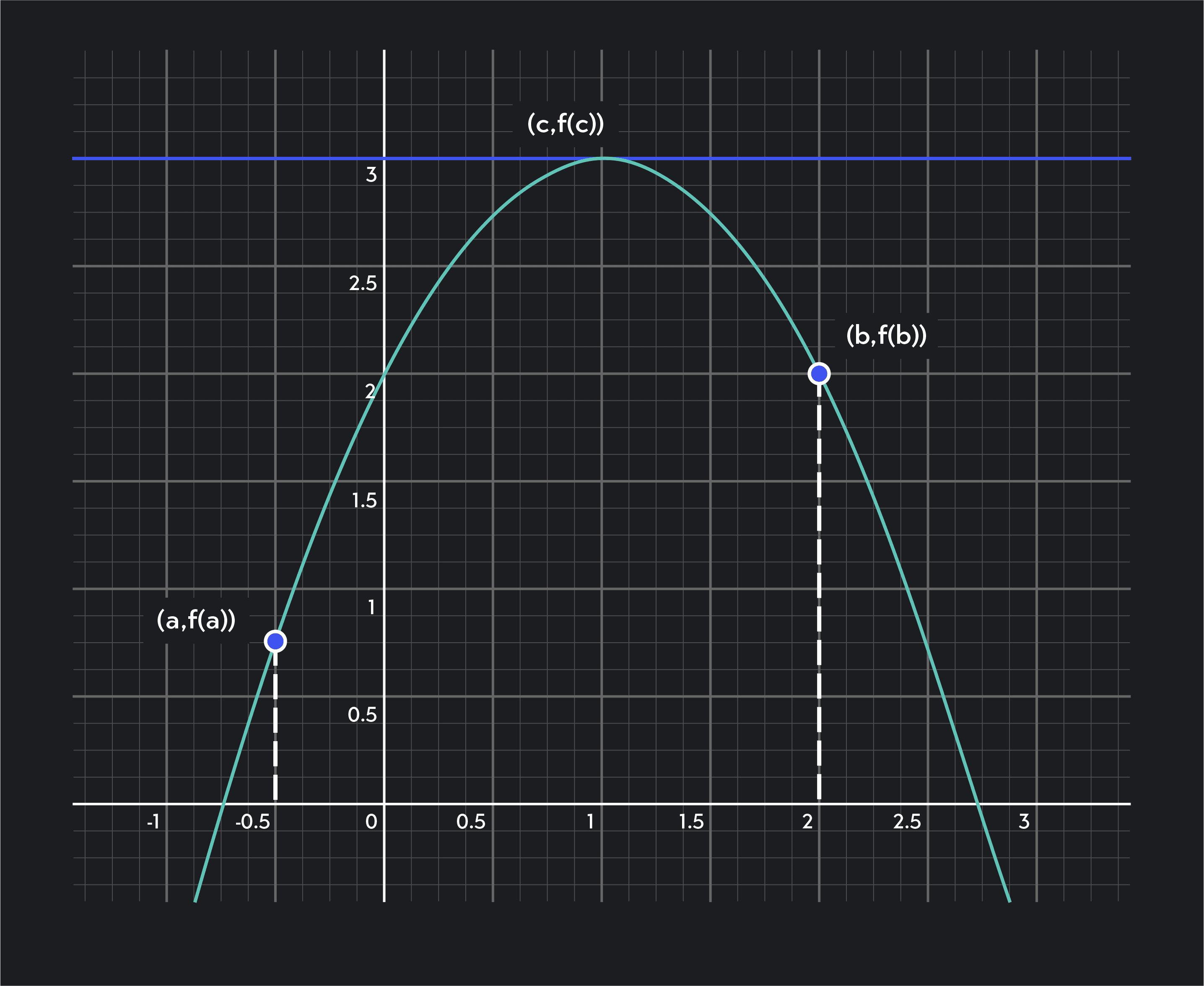

Visualizing this theorem using the Rolle’s Theorem example on the graph above might be helpful. This graph depicts the function .

The 3 Rolle’s Theorem conditions are satisfied:

The 2 points in black, and , have the same y-value.

Our parabola function is differentiable on .

Our parabola function is continuous on .

Notice how a horizontal tangent line is at the point

Michel Rolle (1652 - 1719) is best remembered for Rolle’s Theorem, but he also had several other mathematical contributions. For example, he created the notation to represent the nth root of .

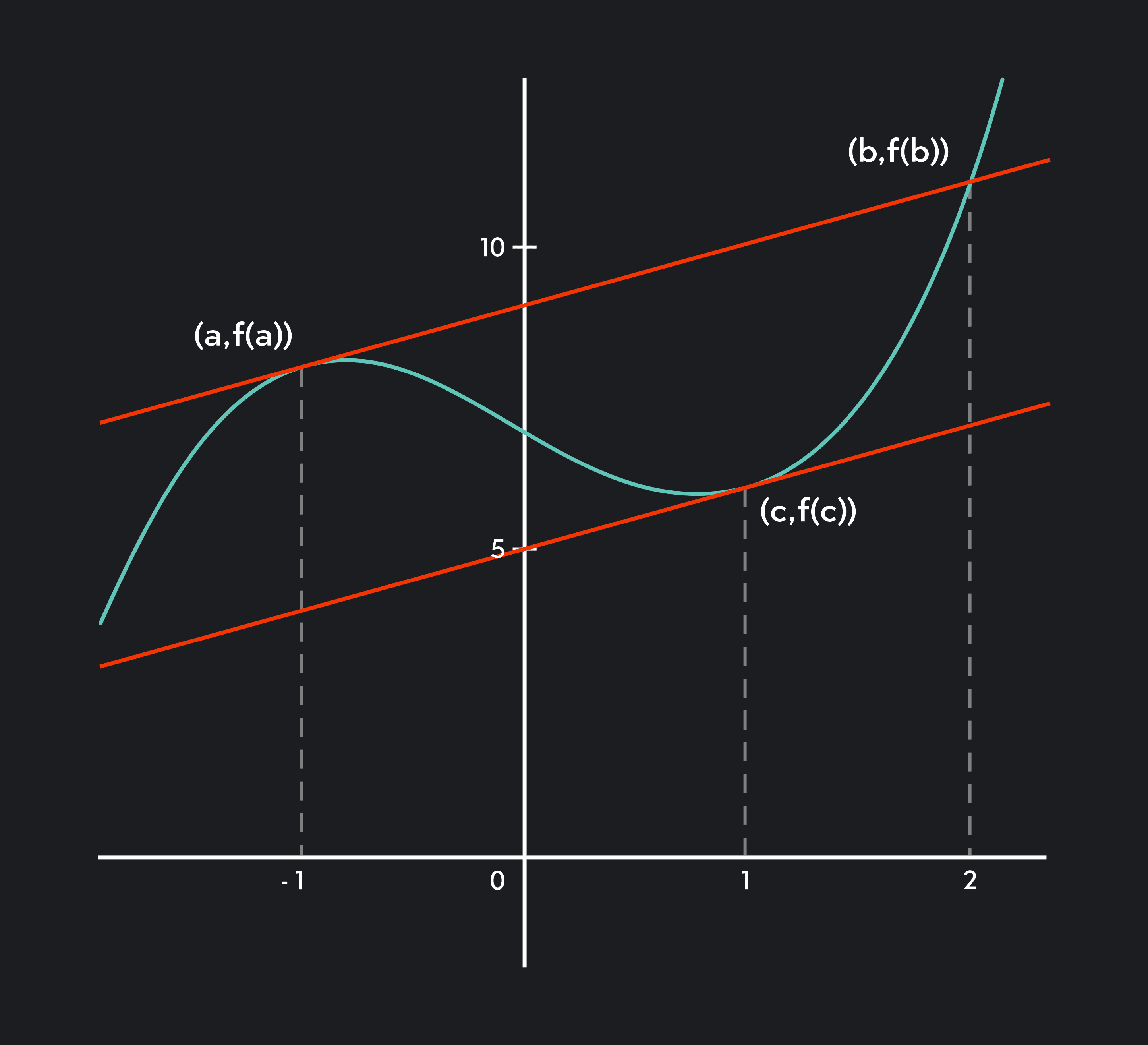

What is Lagrange’s Mean Value Theorem? Lagrange’s Mean Value Theorem is an expanded version of Rolle’s Theorem. Consider the graph below to get a visual understanding of MVT calculus.

Lagrange’s Mean Value Theorem states that if the function is continuous on the closed interval and differentiable on the open interval , then there exists a point in the interval such that .

In other words, Lagrange’s Mean Value Theorem states that a continuous and differentiable interval of a function must have a point where the tangent line’s slope is equal to the average slope over the interval. (This is also known as the slope of the secant line.) On a graph, this presents itself as 2 parallel lines.

Rolle's Theorem adds the extra condition that the average slope is 0. This means the function has a point where the tangent line’s slope is 0 within the given interval.

Let’s learn how to do Mean Value Theorem problems by using the graph above, where . Let and . This function is differentiable on and continuous on , so the 2 conditions are satisfied.

Our next step is to find the average slope over the interval, which is . To find the point at which , we can set the first derivative equal to 1.

So, we have:

The open interval does not include its endpoints, so is outside our interval. So, is the point where on .

For Rolle’s Theorem to hold true, the 3 following conditions must be satisfied. You’ll notice this theorem sounds similar to Lagrange’s Mean Value Theorem, since Rolle’s Theorem is a special case of the Mean Value Theorem.

The function is differentiable on .

The function is continuous on .

If these 3 conditions are true, then there exists at least 1 in the interval where .

Note the difference between and . The interval is open, meaning that it doesn’t include its endpoints and . The interval is closed. This means it does include its endpoints and .

If you can trace a curve on a graph without lifting your pencil, the function is continuous at every point. If you cannot trace a curve without lifting your pencil, the function is discontinuous at that point. This means it has a hole, break, jump, or vertical asymptote.

A function is continuous at the point if:

exists

exists

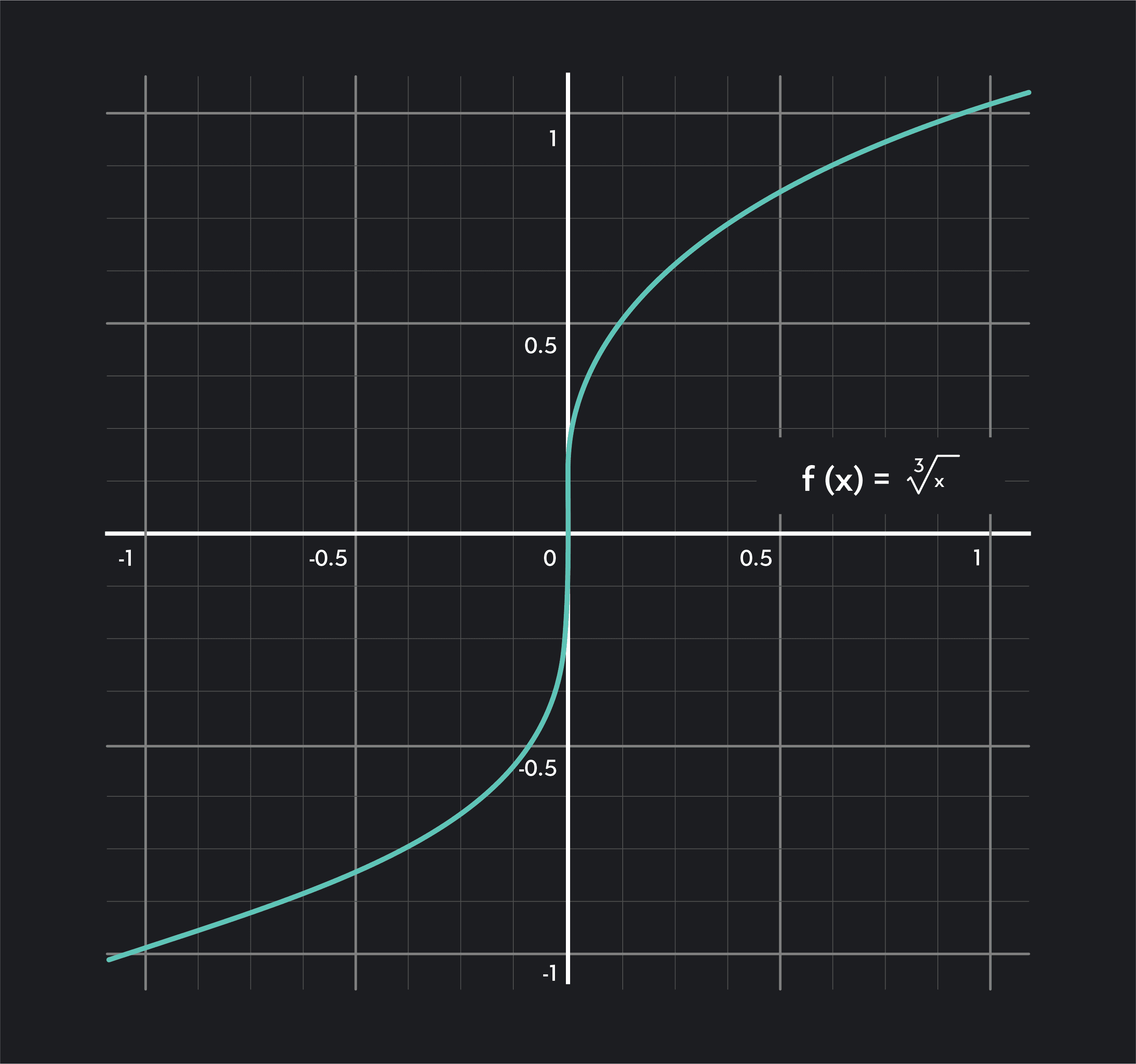

What does it mean for a function to be differentiable? If a function is differentiable, its derivative exists at every point in its domain. This means that we can find the derivative at every point on the function’s curve.

If a function is differentiable at a point

This limit looks like this:

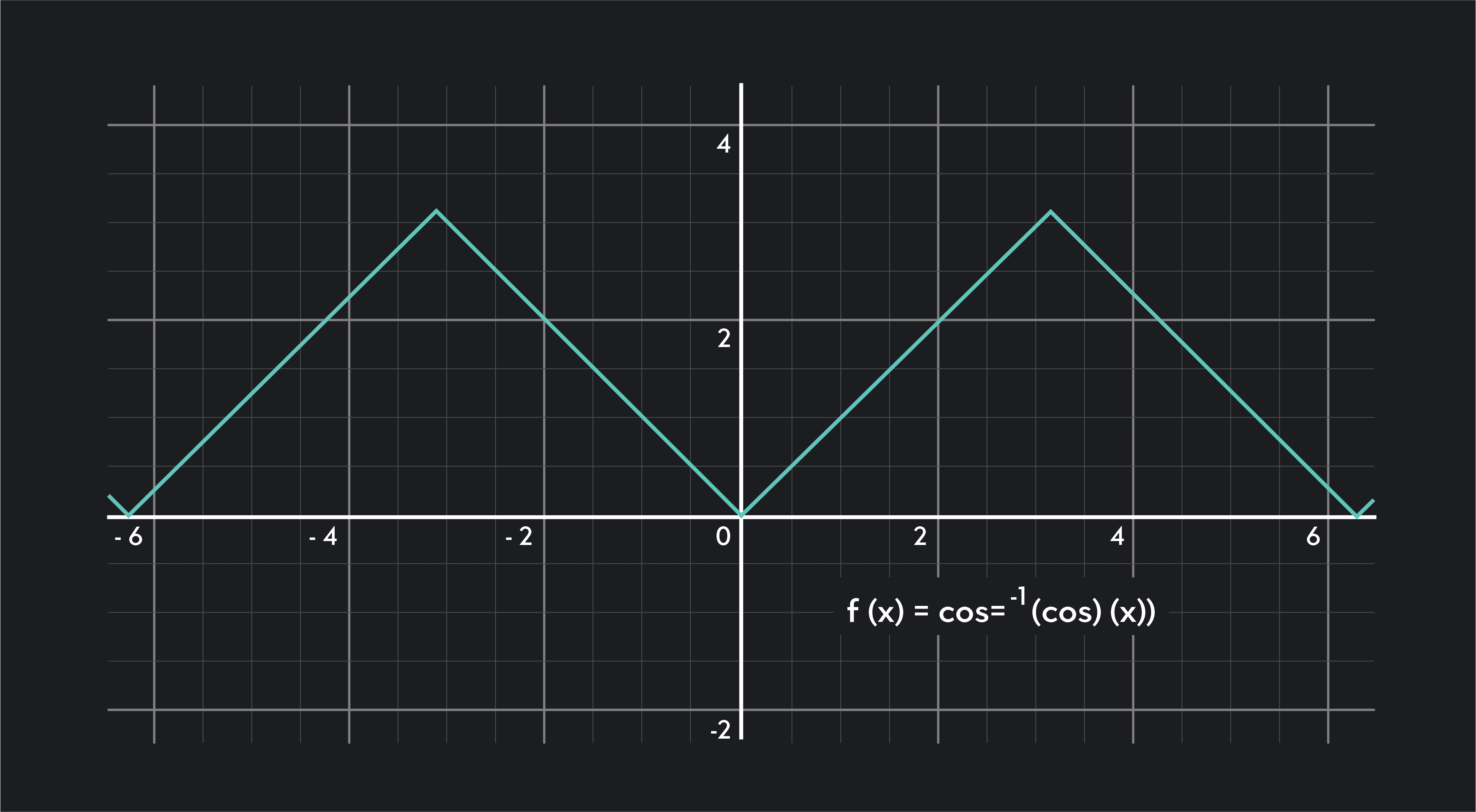

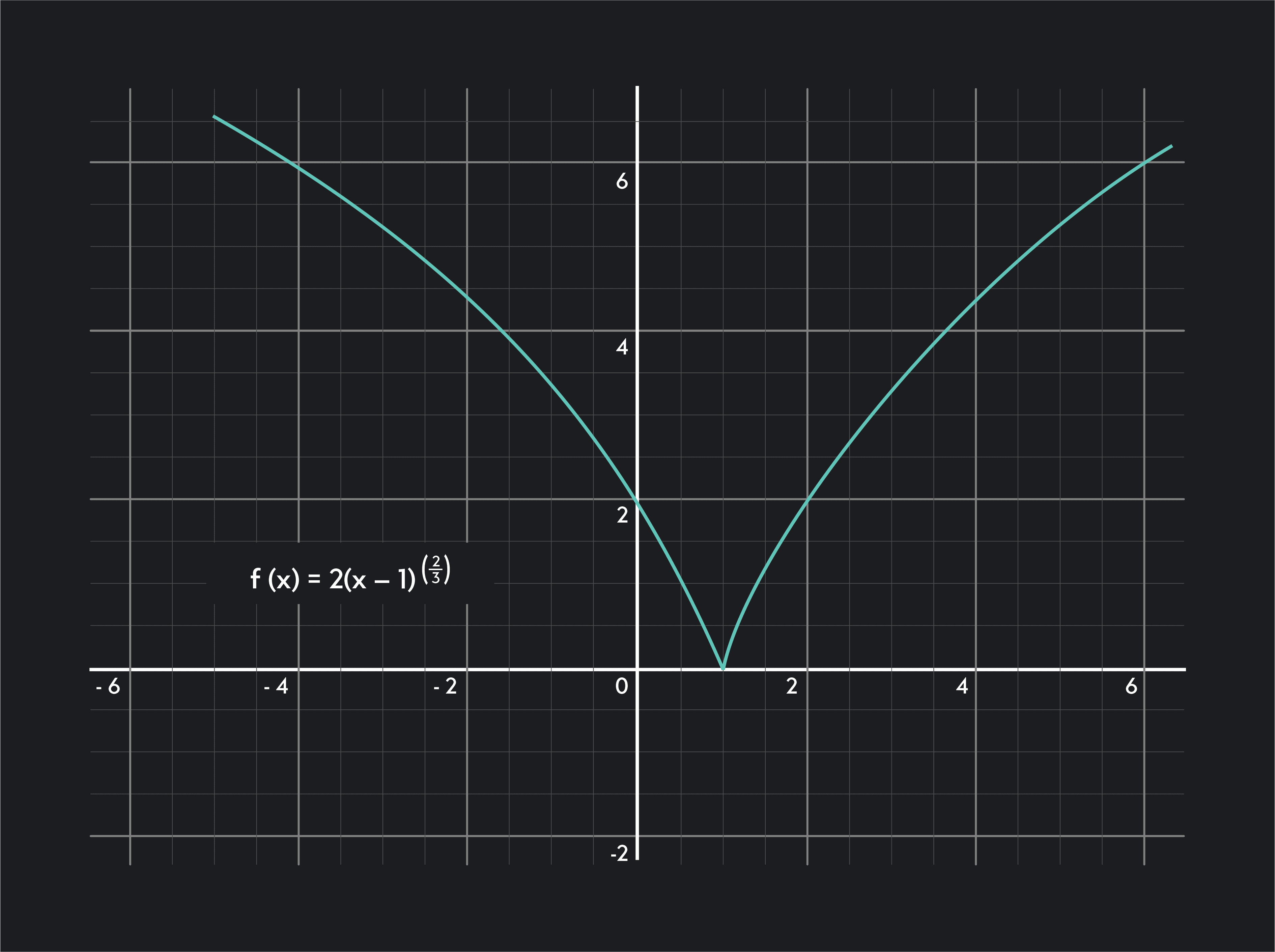

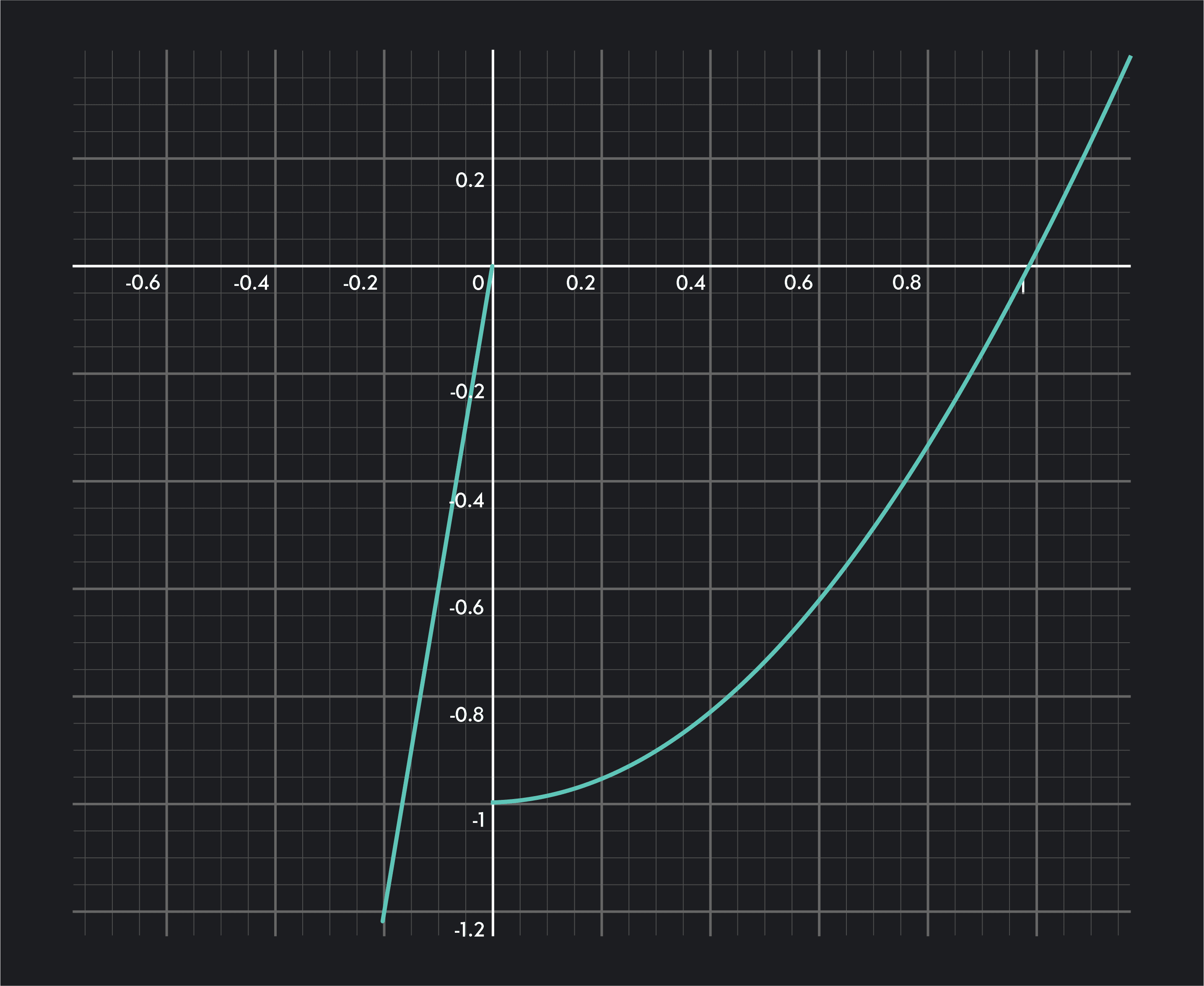

Knowing what corner points, cusps, vertical tangents, and discontinuities look like on a graph can help you identify the points where a function is not differentiable.

Here are some examples:

A corner point looks like 2 line segments of a function that meet at a sharp point. The slope to the left of a corner point is different from the slope to the right of the corner point.

A cusp looks like 2 curves that meet at a sharp point. The slope to the left of a corner point is different from the slope to the right of the corner point.

At a vertical tangent, the slope of the tangent line approaches

For example, at a jump discontinuity, the curve jumps abruptly to another point on the graph. The right and left-hand limits are not equal at this point.

To start our proof of Rolle’s Theorem, let the function

Since is continuous on , by the Extreme Value Theorem, we can say there must be an absolute maximum and minimum on . If these occur at the endpoints and , then is a constant function, and so at any point.

Then every point satisfies Rolle’s Theorem, since we can pick any number in and have .

Suppose instead the maximum occurs at an interior point

Similarly, suppose instead the minimum occurs at an interior point

Let’s try some math problems using Rolle’s Theorem.

Let . Does Rolle’s Theorem guarantee the existence of such that on ? If so, find .

Since is a polynomial function, is continuous on and differentiable on . The first 2 conditions of Rolle’s Theorem are satisfied. Does ?

Let’s check:

, and , so . All 3 conditions are satisfied, so Rolle’s Theorem holds and guarantees the existence of such that on .

To find , we’ll set equal to 0 and solve. Using the power rule, we have

Let . Does Rolle’s Theorem guarantee the existence of such that on ? If so, find .

Since is a polynomial function, is continuous on and differentiable on . The first 2 conditions of Rolle’s Theorem are satisfied. Does ?

Let’s check: , and . Since , Rolle’s Theorem does not guarantee the existence of such that on .

Let . Does Rolle’s Theorem guarantee the existence of such that on ? If so, find .

The function is undefined at , since an infinite discontinuity is at . Thus, is not a continuous function and the first 2 conditions are not satisfied, Rolle’s Theorem does not guarantee the existence of such that on .

Here are a few commonly asked questions about Rolle’s Theorem.

In math, Rolle’s Theorem is a vital tool for solving calculus problems that involve analyzing the behavior of function. It is also used to help prove the Mean Value Theorem and other important theorems. In physics, we can use Rolle’s Theorem to determine a projectile's trajectory. We can also use it in architectural settings to plan the construction of domes.

The converse of Rolle’s Theorem is not true. The converse of Rolle Theorem supposes that the function is continuous in and is differentiable in , and states that if for some in , then .

This statement is not true. If for some on , it is possible to find points and where .

Consider the graph below as an example. We can see that , yet .

Outlier (from the co-founder of MasterClass) has brought together some of the world's best instructors, game designers, and filmmakers to create the future of online college.

Check out these related courses:

Calculus

Learn the definition of relative extrema, how to identify points of relative minima and maxima, and practice your knowledge with worked examples.

Subject Matter Expert

Calculus

Learn what the second derivative test is and the steps to find it. Included are visual graphs, examples, and tests.

Subject Matter Expert

Calculus

Learn what the squeeze theorem is, how to prove it, and practice with some examples and tips.

Subject Matter Expert