Economics

Understanding the Supply Curve & How It Works

Learn about what a supply curve is, how a supply curve works, examples, and a quick overview of the law of demand and supply.

Alejandro Diaz Herrera

Subject Matter Expert

Economics

05.31.2022 • 9 min read

Subject Matter Expert

Learn what the free rider problem is, its relationship with public goods, and read an example using a prisoner’s dilemma game plus five solutions.

In This Article

In economics, a free rider is somebody who benefits from a good or service without paying or contributing to its production or upkeep. If you’ve ever participated in a team project, you’ve likely encountered a free rider. The free rider is the person on the team who does little to no work but still benefits from a good grade or the praise of whoever assigned the project. With little to no cost to themself, the free rider can reap a reward as a consequence of costs incurred by others.

Here are some other examples of free-riding:

A person who jumps the turnstile and rides the subway for free

A resident who doesn’t volunteer time to a neighborhood association, yet benefits from the association’s activities

A citizen who does not vote because they know enough people will show up to vote for their favored candidate

A country that emits a lot of greenhouses gasses, but incurs a disproportionately small amount of the costs

The free rider problem is a general term used to describe markets and interactions where the potential for free riding exists. When a market is susceptible to free riding, it can lead to market failure, meaning there will be an inefficient allocation of goods or services in the market. Sellers lose their incentive to sell because too many consumers are able to access the product for free. As a result, sellers will pull out of the market, and there will be an underprovision of goods—i.e., too few goods produced.

The free rider problem is especially common in markets for public goods.

A public good is a good or service that exhibits the two key characteristics of being non-rival and non-excludable. Non-rival means that one consumer’s consumption does not affect the availability of the good or service for another consumer. Non-excludable means that those who are unwilling to pay for the good or service cannot be prevented from consuming it.

The non-excludability of public goods is what leads to market failure caused by free riding. If consumers are able to access a good for free, why would they pay for it? And if sellers can’t get buyers to pay for a good, how can they stay in business? When buyers are able to access the good for free—and when sellers are unable to earn sufficient revenues to stay in business—the market breaks down.

| EXCLUDABLE | NON-EXCLUDABLE | |

| RIVALROUS | Private Goods - Housing, food, clothing, cars | Common Pool Resources - Forests, fish in the sea |

| NON-RIVALROUS | Club Goods- Certain types of intellectual property, subscription TV, uncongested toll roads | Public Goods -National defense, clean air, public roads, street lights, Wikipedia |

Because public goods suffer from the free rider problem, they tend not to be distributed by private firms in competitive markets. Instead, the government, non-profits, or other charitable organizations often provide public goods.

Here are three examples of public goods that would suffer from free riding in a competitive market.

Wikipedia is a public good because it is non-rival—one person’s use of the service doesn’t prevent somebody else from using it. It also is non-excludable—everyone can access Wikipedia regardless of whether they contribute to the site or not. Because Wikipedia wants to make its service publicly available (non-excludable), it is difficult for them to operate as a profit-seeking company. This is part of the reason why Wikipedia operates as a non-profit foundation instead of a firm.

National defense is also a public good. Consider a missile defense system that protects an entire state. Once the defense system is up and running, one resident’s utility from the defense system does not infringe on the utility of other residents. The defense system is non-rivalrous in this way. It is also non-excludable because non-payers can’t be prevented from benefiting from the system. If a private company were to try to “sell” a missile defense system to residents of a state, the residents would have an incentive to free ride.

Lighthouses are another public good. When one boat utilizes the light from a lighthouse, it does not reduce the availability of light for other boats (lighthouses are non-rivalrous). Lighthouses are also non-excludable since they cannot shine their light on boats that pay and be off for boats that don’t. Any boat in the proximity of the lighthouse can benefit from its light.

As a public good, governments or non-profits operate most lighthouses. The Coast Guard maintains and operates lighthouses in the US, often with help from private donations and charitable organizations.

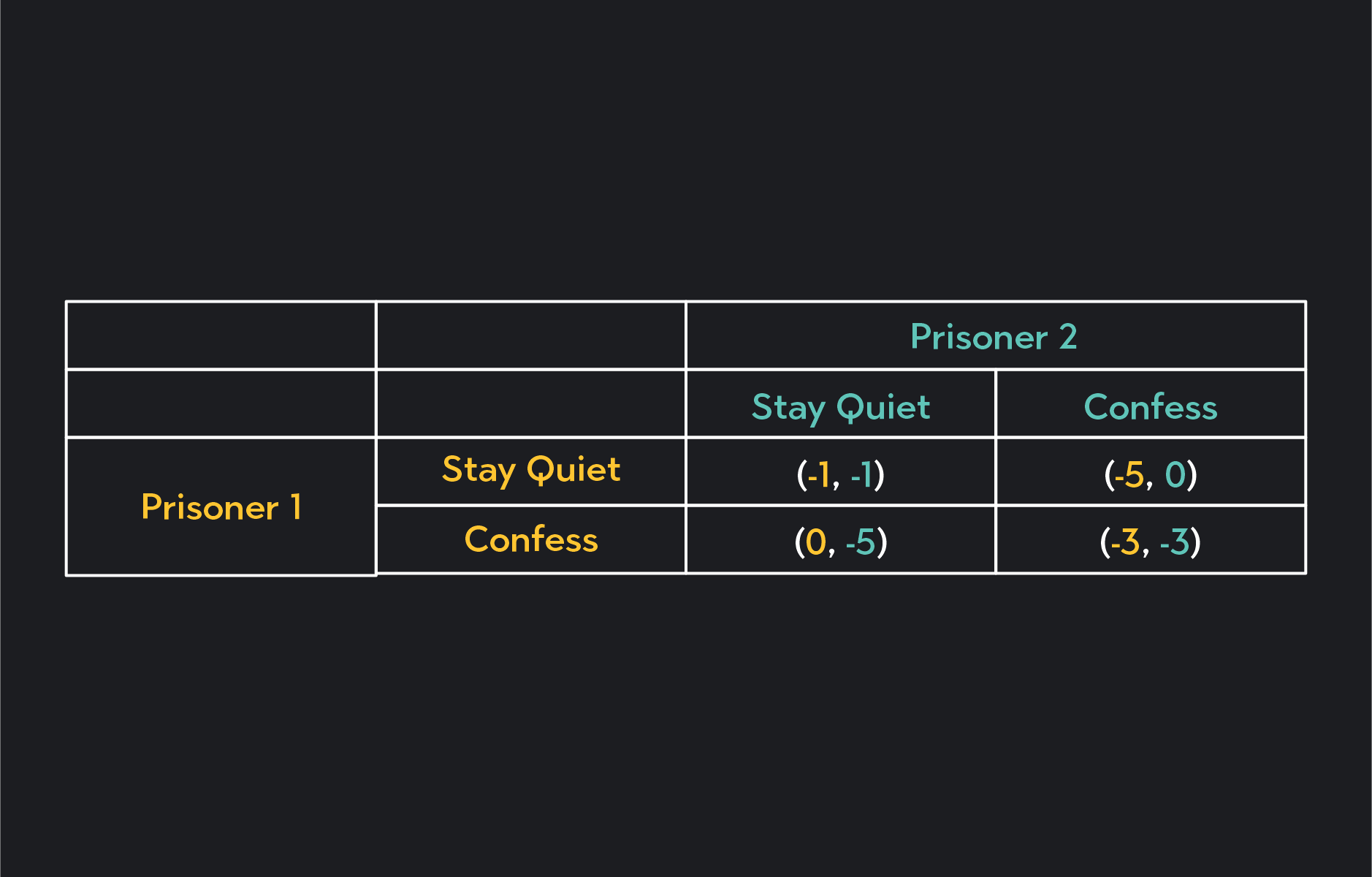

The incentives behind free riding can be demonstrated using a model from game theory called the Prisoner’s Dilemma. The Prisoner’s Dilemma is used to demonstrate interactions where two people (or two groups), each acting rationally and in their own self-interest, can make decisions that lead to outcomes that are suboptimal for all parties involved.

The classic example of the Prisoner’s Dilemma involves two bandits who have been arrested on suspicion of robbing a bank. The sheriff who makes the arrest does not have enough evidence to charge the bandits with the crime, but he does have enough evidence to send both bandits to jail for one year on a minor charge. If the sheriff gets either prisoner to confess to the robbery, he can sentence the prisoners to up to five years in jail.

As part of a plan, the sheriff separates the prisoners into two separate rooms and offers them each the same deal. If one of the bandits confesses to the robbery, he will be released from prison for his cooperation and the other prisoner will be sent to jail for five years. If neither prisoner confesses to the crime, both prisoners will go to prison for one year. If both confess to the crime, the prisoners will each go to prison for three years. Not knowing what the other will do, the prisoners in this scenario are incentivized to confess.

Regardless of what the other prisoner chooses to do, confessing will lead to a better outcome. If the other prisoner stays quiet, it is better to confess since going free is better than spending one year in jail. If the other prisoner confesses, confessing is still the better choice, because three years in prison is better than five years in prison. Following this logic, both prisoners may choose to confess and will end up serving three years in prison, which is an outcome that is worse than if they had both stayed quiet.

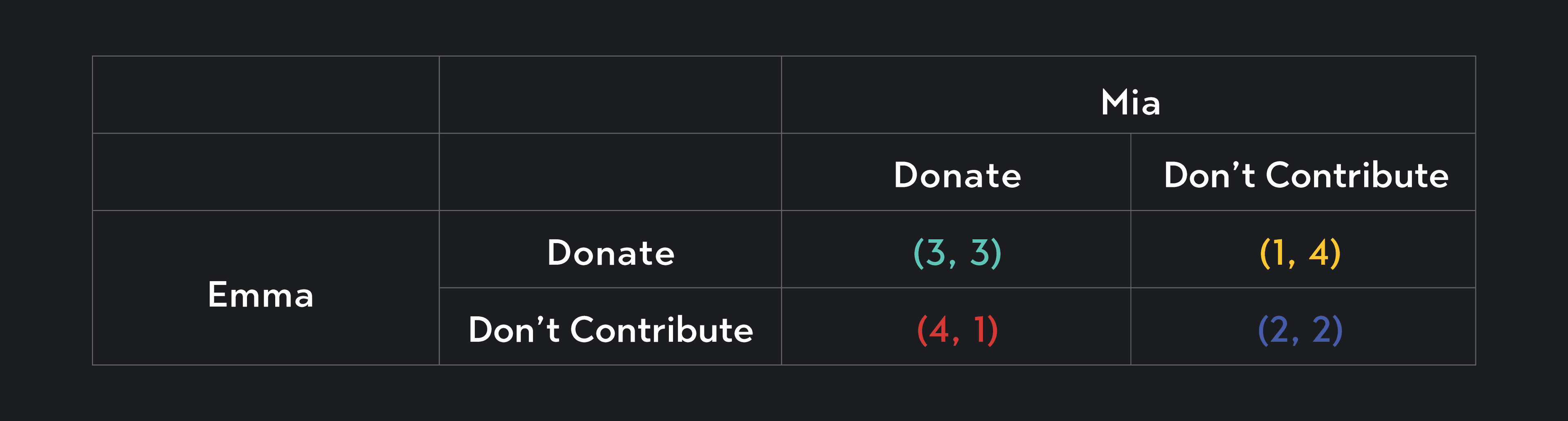

Suppose two friends, Emma and Mia, are visiting their favorite park. They arrive at their usual spot in the park—a pond surrounded by park benches, trees, and flower beds—but they notice the area has become less serene. Harmful algae are growing in the water, there is litter around the park benches, and no one has tended the flower beds. Just as they are taking in the mess, a volunteer comes to them and hands out a flyer with a link to donate a fixed dollar amount to park maintenance and cleanup. Emma and Mia each have a choice to make. They can donate or they can choose not to contribute.

The matrix below models the choices and payoffs for Emma and Mia.

If both choose to donate, the net benefit (or net gain) will be 3 for Emma and 3 for Mia. The green cell shows this outcome. The net benefit is a figure representing the benefit each person gets from the improvements to the park, minus the amount they had to donate.

If Emma chooses to donate, but Mia chooses not to, the net benefit for Emma is 1, and the net benefit for Mia is 4. The orange cell shows this outcome. Since there’s less money donated to the cleanup effort, there are fewer improvements to the park. Emma is still donating, so her net benefit is lower than the scenario where both friends are donating, but Mia’s net benefit is actually higher. Even though the improvements to the park are limited, she has not had to pay anything to get them.

The opposite occurs if Mia donates, but Emma does not. In this case, Emma’s net benefit is 4, and Mia’s net benefit is 1. The purple cell shows this outcome.

If Emma and Mia both choose not to contribute, they will each receive a net benefit of 2. There is even less money for the cleanup efforts, but neither has had to pay for any improvements. The blue cell shows this outcome.

In scenarios like this, people can actually be incentivized not to contribute. Think about Emma’s options. If she thinks Mia will donate, Emma’s net benefit will be 3 if she donates or 4 if she chooses not to. Since 4 is better than 3, this benefit may tempt her to not contribute. If she thinks Mia won’t contribute, the outcome still motivates Emma to not donate, since a net benefit of 2 is better than a net benefit of 1. Regardless of what Mia chooses, if Emma is looking out for her best interests, she will choose not to donate.

The exact same logic applies to Mia. Mia’s best choice is also to avoid contributing, and instead, benefit from the costs and efforts of others. But now, consider looking at what happens. Both Mia and Emma will choose not to contribute to the cleanup, and they will be guaranteed to each receive a net benefit of 2. If instead, they had both decided to donate, they would have been better off. They could have each received a net benefit of 3 instead of 2.

The incentives and outcomes demonstrated by the Prisoner’s Dilemma can be extended to models where the number of people interacting is greater than two. Suppose 50 fishing boat companies have a choice of whether to pay a $5,000 service fee for maintaining and operating a lighthouse. From the perspective of each company, there is an incentive to free ride and to try to benefit from the service fees paid by others. But collectively, all boats would be better off if they each pay the fee.

There are several ways to address the rider problem.

As we mentioned earlier, the government can provide public goods that are susceptible to free riding instead of private firms.

Non-profits and other charitable organizations can also provide public goods, so long as there are enough funds to make the good or service available.

Companies can find ways to mitigate the free rider problem by making changes to their product. For example, a subway turnstile discourages most people from sneaking on to the subway and riding for free. If Wikipedia wished to do so, they could add a paywall to make their service excludable or they could seek revenues elsewhere by placing paid advertisements on their site.

Certain market interventions might also help to discourage free riding. For example, consumers of a non-excludable good or service could be required to sign a contract enforceable by law that obligates them to pay for what they consume. The government could also tax or subsidize goods or services in a way that ensures that sellers have an incentive to continue their products or in a way that ensures that consumers pay for what they consume.

Sometimes altruism, social norms, and social pressures are the best remedy for the free rider problem. If people are altruistic, they look beyond their immediate self-interest and derive pleasure from doing things for others. Social norms and social pressures work similarly. You would be less likely to free ride in a team project if your team members were your close friends or if you were afraid of being shunned or scorned by them as a result of your actions.

Public campaigns, such as campaigns to get out the vote and to keep neighborhoods clean, can often discourage free riding because they give people a sense of pride or social responsibility beyond what is in their limited self-interest. If social preferences and obligations motivate individuals beyond their narrow self-interest, they will often resist free riding even when there is an opportunity to do so.

Outlier (from the co-founder of MasterClass) has brought together some of the world's best instructors, game designers, and filmmakers to create the future of online college.

Check out these related courses:

Economics

Learn about what a supply curve is, how a supply curve works, examples, and a quick overview of the law of demand and supply.

Subject Matter Expert

Economics

This article gives a quick overview of perfect competition in microeconomics with examples.

Subject Matter Expert

Economics

This article is a comprehensive guide on the causes for a demand curve to change. Included are five common demand shifter examples.

Subject Matter Expert