In This Article

Who Was Sigmund Freud?

Sigmund Freud’s Major Works

Freud’s Structure of the Human Mind

A Selection of Key Freudian Theories

Criticism of Freud’s Theories

Freud’s Importance

Who Was Sigmund Freud?

There are certain figures whose names become so central to the popular understanding of their field that they can almost seem to stand for the whole of it. Sigmund Freud is one of these names. Born in 1856 in the Austrian Empire, Freud was a neurologist who was particularly interested in neuropathology. Through both his therapeutic practice and his theoretical writing, Freud was the driving force behind the emergence of psychoanalysis, a method for understanding the human mind and its ailments which had, and in certain ways continues to have, a profound impact on a wide range of activity beyond the field of mental health.

Sigmund Freud’s Major Works

Over the course of his five-decade career, Freud wrote more than a dozen books and hundreds of essays and articles. Let’s take a quick look at four texts which stand out as particularly significant within his larger body of work.

In The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), one of his earliest books, Freud introduced the idea he remains most known for: the unconscious mind, a zone of mental activity outside of our conscious access which he believed held the key to understanding a wide array of mental illnesses. Freud argued that dreams provide a unique window into the unconscious mind, and he explored this uncharted territory by dividing dreams into manifest content (the surface-level details and storyline of a dream) and latent content (the psychological meaning of a dream).

Freud’s next major work, The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901), saw him continue to examine unconscious mental activity by turning his attention to repressed memories and what we have come to know as Freudian slips. A Freudian slip is an accident in speech, action, or memory that Freud thought revealed the contents of the unconscious mind. For example, if a teenager is away at camp and asks “is daddy coming?” instead of “is Danny coming?”, Freud might argue that this slip indicates that they unconsciously wish their father were with them, not their friend Danny.

In The Future of an Illusion (1927), a brief but dense book, Freud turned his focus from the individual to broader social dynamics, as he applied his psychoanalytic theories to religion. Though he ultimately rejects organized religion as a socially harmful illusion, The Future of an Illusion deals largely with understanding why religion has remained such an enduring institution.

Freud would return to religion, and other large-scale social forces, in one of his most enduringly popular books, Civilization and Its Discontents (1930). Here, he begins by picking up where The Future of an Illusion left off, examining religion via the “oceanic feeling,” the individual desire for a sense of wholeness with the world, which Freud finds relates back to the earliest moments of life. He then moves on to examine in more detail the tension that exists between other desires of the individual and the civilization of which they are a part.

Freud’s Structure of the Human Mind

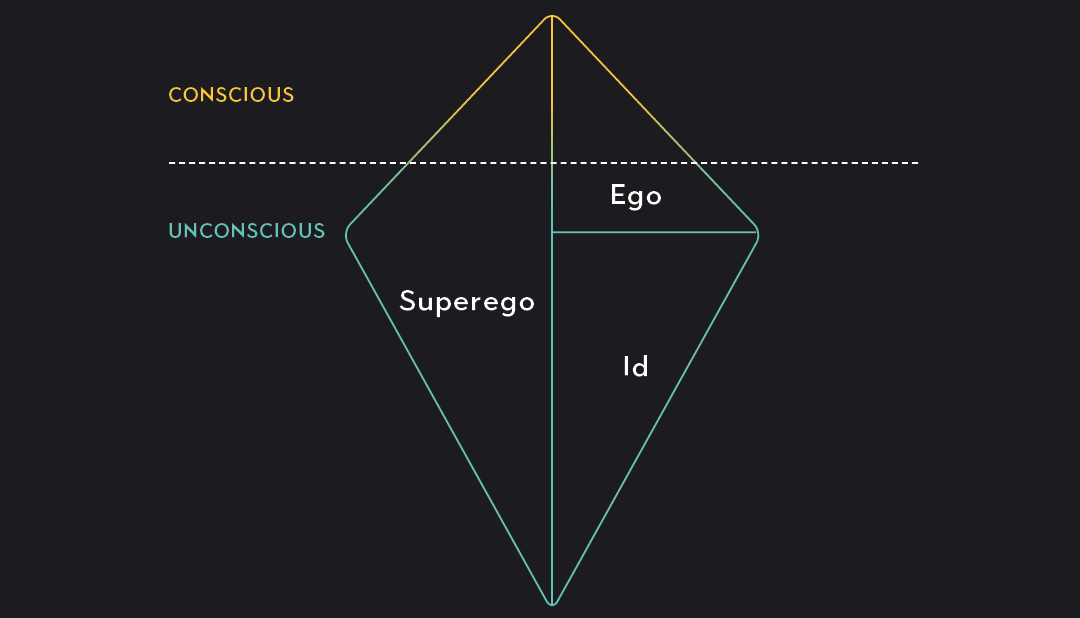

If you’ve ever blamed something on an unconscious desire, you have Freud to thank for that. As mentioned above, Freud theorized that there are conscious and unconscious worlds in the mind. The conscious mind is home to everyday mental activity, what we normally just call “thinking.” In contrast, the unconscious mind (and its less-discussed neighbor, the preconscious mind) is the site of an enormous amount of mental activity beyond our access. He further divided the pre- and unconscious minds into the id, the ego, and the superego. The id represents our most basic urges, motivated by pleasure; the superego is our conscience; and the ego is the mediator between our primitive desires and our ideals. The id is like a child, unconcerned about consequences and driven by pleasure; the superego is the angel on our shoulder, our moral compass.

Freud thought that neuroses occur if someone is imbalanced—if their id or superego has too much control. He believed that the ego worked to restore balance between the id and superego by using a number of different defense mechanisms. These operate unconsciously, protecting us from having to experience conscious discomfort from the conflict between our id and superego.

While Freud identified many defense mechanisms, here are a few key ones you may have encountered before:

Denial: refusal to accept reality

Projection: accusing others of having thoughts or desires that the accuser actually has

Rationalization: using acceptable-sounding reasons to justify something instead of admitting the real, less acceptable reasons

Regression: using coping strategies from less mature developmental stages

Sublimation: using socially acceptable channels to redirect unacceptable desires

Note that not all defense mechanisms are created equal, and they depend heavily upon context. While denial is usually not very constructive (you can’t live in a fantasy world forever), sublimation can at times be quite healthy (someone feels the urge to be unfaithful and sublimates those sexual urges into exercise, becoming healthier while maintaining the relationship they care about).

A Selection of Key Freudian Theories

Talk therapy

Freud’s early forays into talk therapy were undertaken while working with his colleague Josef Breuer, a Viennese physician, and Breuer’s patient, known under the pseudonym Anna O. She came to Dr. Breuer with the symptoms of “hysteria.” While no longer an acceptable diagnosis, at the time, “hysteria” was a catchall term for many illnesses that women suffered (one which carried markedly sexist overtones). Dr. Breuer and Anna O. found that simply talking about the troubling experiences in Anna’s life helped to relieve her symptoms. Anna O. referred to this phenomenon as the “talking cure.”

While Freud never spoke to Anna O. himself, he found Breuer’s work fascinating and co-authored a book with him called Studies on Hysteria (1895). Freud pushed the implications of Breuer’s work further and argued that Anna O.’s symptoms were due to sexual abuse she had repressed as a child. Dr. Breuer disagreed with Freud and the pair split, with Freud diving headfirst into the development of talk therapy and analysis of the unconscious mind.

Psychosexual development

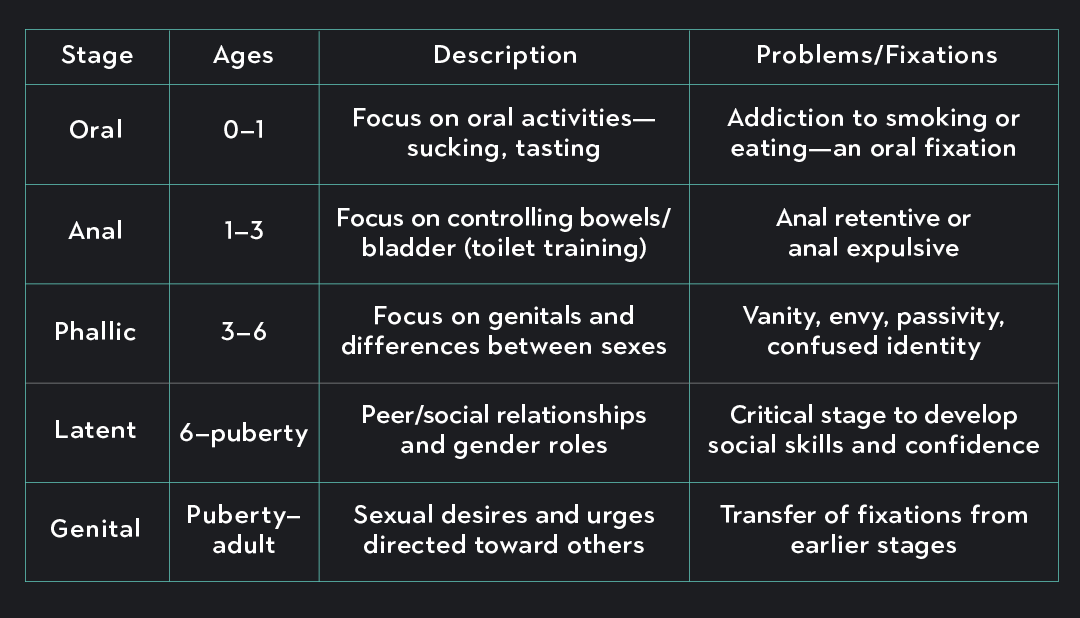

Freud saw personality through a developmental lens. He focused intensely on early childhood experiences and theorized about how these experiences shape our adult personalities. He divided development into five psychosexual stages: the oral, anal, phallic, latent, and genital stages. He believed that if we aren’t properly cared for during these periods, we can become fixated on a stage. The classic talk therapy question—“tell me about your mother”—was an inroad to discovering at which stage your mother might have failed you.

For Freud, the oral stage lasted from infancy to one year. In this stage, the child must be weaned. For an adult whose weaning went wrong, you might see an addiction to smoking or eating—an oral fixation.

The anal stage, between ages one and three, is all about toilet training. If a child has issues during this stage, the adult might be anal retentive (overly neat and uptight) or anal expulsive (messy and prone to outbursts). Who knew that toilet training could impact how clean your house is as an adult?

From ages three to six, we find ourselves in the phallic stage. Here, children learn about the difference between female and male bodies. Little boys develop the Oedipus complex, in which they feel desire for their mothers and jealousy of their fathers. This jealousy is coupled with the emergence of castration anxiety, arising from the fear the father would retaliate by castrating his son, stealing away his newly discovered difference. If the little boy does not resolve his Oedipus complex by identifying with his father (as a way to indirectly desire his mother), then he may turn out to be ambitious and vain.

What about little girls? Of course, they become aware of the difference between male and female bodies too, and for Freud, their response was equivalently complex. In contrast to boys, who worry that something will be taken from them, girls worry that something already has been. This “penis envy,” as Freud termed it, results in young girls becoming angry with their mother for not providing them with a penis, leading into a long series of anxieties commonly resolved only through marriage or motherhood. Freud’s younger colleague, Carl Jung, would explore this dynamic in more detail, eventually dubbing it the Electra complex (a term Freud himself rejected).

From ages six to puberty, we get a break from the psychosexual madness as we enter the latency period. During this time, kids work on peer relationships and gender roles and forget about sex for a little while.

Finally, from puberty through adulthood, we find ourselves in the genital stage. During this period, Freud believed that our incestuous desires for our parents reemerge and we take those urges and direct them outward toward more appropriate targets (...people our own age who remind us of our parents). At this stage, if you made it through the other stages successfully, you’re a well-adjusted adult. Phew!

Criticism of Freud’s Theories

In medical and scientific circles, Freud’s theories have generally not withstood the test of time. One of the biggest problems with Freud’s work is that it is unfalsifiable—it can’t be proven to be wrong. When using the scientific method, your hypotheses must be falsifiable. Otherwise, how can you test them? Consider the Oedipus complex: Freud argues a child unconsciously desires his mother. How could we prove or disprove such an unconscious desire? By its very nature, an unconscious desire is hidden. We can’t simply ask the child, because even if they contradict the theory, Freud would say that they’re simply unaware of their hidden desire. We can’t measure it objectively, so there’s no way to tell whether this supposed unconscious desire is or is not present in the child.

Another commonly raised criticism involves the fact that Freud developed his theories from a small number of case studies. Not only that, nearly all of his patients within this small sample size were members of the Viennese bourgeois, what we’d call today the upper middle-class—nowadays, we know better than to make inferences about all of human experience based on small, homogeneous research populations.

Freud has also faced criticism for ignoring the forces of culture and learning in certain theories, as he focused heavily on early childhood, biology, and unconscious drives. Despite this narrow personal and social context, Freud routinely drew sweeping conclusions intended to apply to the whole of humanity based on the material which emerged from his analysis. When measured against contemporary medical and scientific standards, his evidence can appear both lacking and ungeneralizable.

Finally, Freud has been criticized for promoting sexist ideas about women. There are indications in his writings that he, like many during his time, considered women to be less capable, more passive, and generally inferior to men. Freud was against women’s emancipation, and some of his ideas, such as his theory of penis envy, reveal that he was very much a man of the 19th century when it came to women’s rights.

Freud’s Importance

While his work has been the subject of intense criticism from every angle—the prior section barely scratches the surface—Freud’s legacy remains significant both inside the field of psychology and beyond it. His innovative way of looking at the mind, considering the unconscious, and using talk therapy have had lasting impacts on the way therapy and psychology look today. The work of many of the 20th century’s leading psychologists, including Carl Jung, Alfred Adler, Erik Erikson, Melanie Klein, and Karen Horney, is impossible to imagine without the foundation his work provided (even if in many cases, the foundation he laid was explicitly rejected). But it could be argued that his legacy was even greater outside of psychology, as his psychoanalytic method—the process of digging beneath the surface to find hidden meanings—had a profound influence on a number of the century’s thinkers and public intellectuals, including Walter Benjamin, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Herbert Marcuse, Frantz Fanon, and Susan Sontag.

Explore Outlier's Award-Winning For-Credit Courses

Outlier (from the co-founder of MasterClass) has brought together some of the world's best instructors, game designers, and filmmakers to create the future of online college.

Check out these related courses: