In This Article

What Is the Hierarchy of Needs?

5 Stages of Need

How We Progress through the Hierarchy

The Expanded Hierarchy

Criticisms of Maslow's Hierarchy

Even if you’ve never sat down in a psychology classroom before, it’s likely that you’ve still encountered a range of the ways in which psychologists have attempted to make sense of the mysteries of the human mind across the last couple centuries. Has a friend ever lamented that they couldn’t pursue a passion because they were too busy with a job they relied on to pay their rent? Whether they knew it or not, they were offering an example of the hierarchy of needs laid out by the American humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow, a model for translating the complex relationships between various human necessities into a simple, intuitive visualization.

Abraham Maslow, developmental psychologist.

What Is the Hierarchy of Needs?

In his essay “A Theory of Human Motivation,” first published in 1943 in the academic journal Psychological Review and subsequently included in Maslow’s book Motivation and Personality (1954), he defined a hierarchy of human needs which in his assertion motivate the behavior of all people. Often represented as a pyramid, this hierarchy begins with basic physiological requirements at the bottom. Subsequently, it proceeds through needs for individual security and stability, personal and social bonds, and different kinds of esteem. And finally, it arrives at a desire for self-actualization at the top. We’ll talk more about the specifics of each of these levels in the next section.

Maslow’s theory was striking from the beginning, as it ran directly against one of the dominant intellectual trends of his day: the cultural relativism first theorized by the anthropologist Franz Boas. Rather than operating on the assumption that local cultures defined the behavior of their inhabitants in fundamental ways, Maslow insisted on the existence of common psychological forms which could be applied to anyone, anywhere.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs continues to be highly influential, especially in the field of positive psychology and related approaches such as Ryff and Singer’s theory of eudaimonic well-being. It’s also remained relevant for certain kinds of psychotherapy, such as Carl Rogers’ humanistic approach, which emphasises the concept of self-actualization. Beyond academia, Maslow’s thinking can often be found in educational and management training circles.

5 Stages of Need

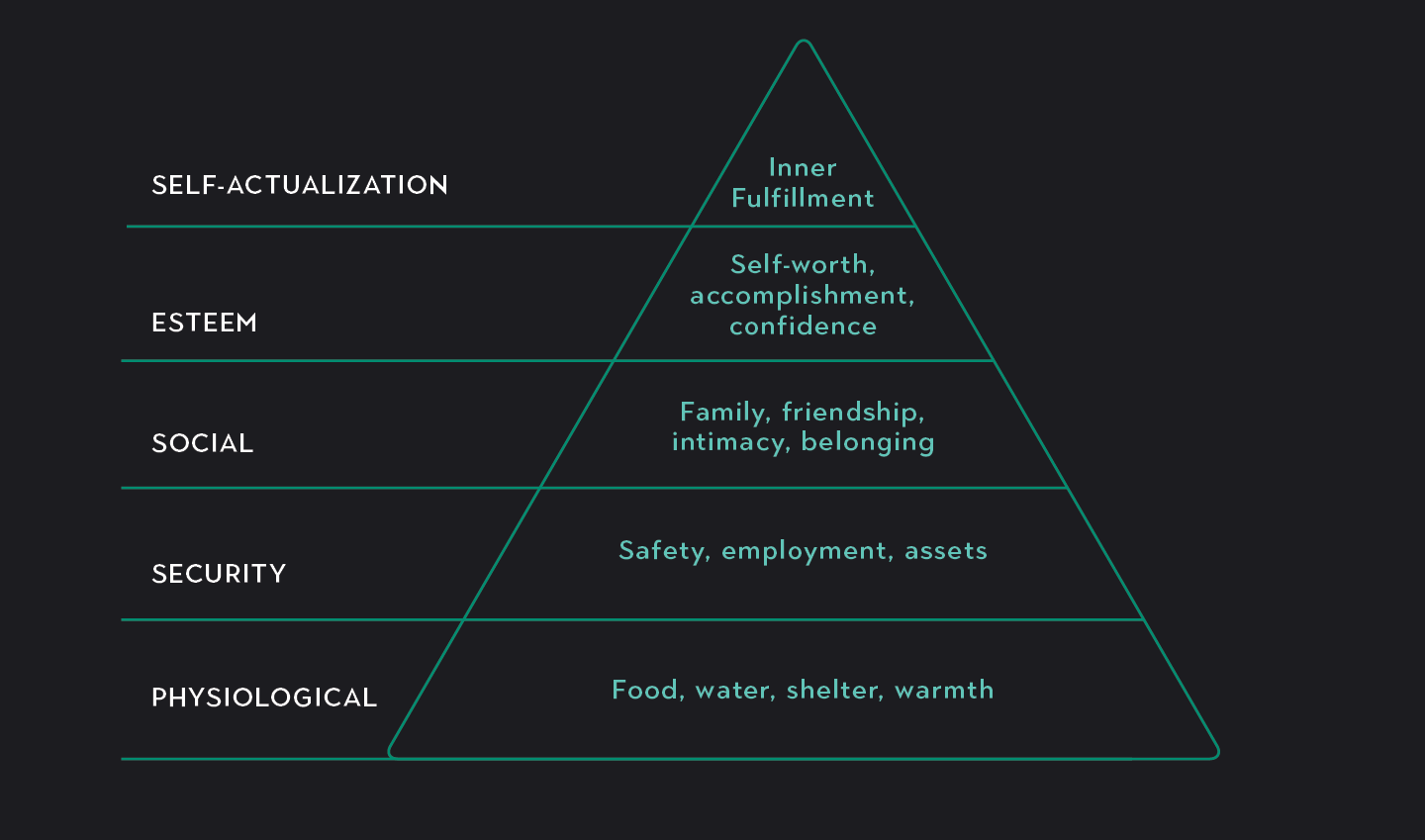

So what actually makes up this pyramid? According to Maslow, all people have the same needs which motivate our behavior. When he first laid out the 5 stages in the original version of “A Theory of Human Motivation,” they were presented as a strict hierarchy, meaning that each level of the hierarchy had to be satisfied before moving on to the next one. Let’s now take a closer look at the specifics of each of these 5 levels:

Physiological Needs: These are the basic biological needs, such as air, water, food, and shelter, that all humans require for survival. Simply put, there’s just no way around these.

Safety Needs: This second level includes personal security, emotional and financial security, and health. In times of insecurity, safety needs will have a major influence on behavior. For example, if you are in physical danger, you will spend all of your resources on trying to get out of that danger, to the exclusion of any needs at higher levels.

Love and Social Belonging Needs: This level is characterized by the need to love and feel loved, as well as to have a reciprocal feeling of belonging. Maslow thought that loneliness, depression, and anxiety were the consequences of not being able to meet these needs, which we can think of as friendship, intimacy, trust, and love.

Esteem Needs: Having satisfied the physical, social, and personal needs of the first three levels, Maslow thought individuals would then be able to turn their energies to achieving stable esteem, both from others and themselves. It’s important to note that this esteem can’t be ungrounded: it has to be based on actual achievements. The need for esteem from others shows up as a desire for recognition, attention, or status, while self-esteem, which Maslow considered the “higher” form of esteem, is seen in the drive to develop qualities such as strength, competence, and independence.

Self-Actualization: This final stage refers to our drive to fully realize our potential. Maslow summed this up with a helpful aphorism: “What a man can be, he must be.” The drive for self-actualization is based on an individual’s goals or motives. Given the extremely personal nature of this need, it’s not surprising that it’s the one Maslow leaves the most open ended. While each individual has to decide on their own what their ideal life looks like, Maslow provides a broad selection of examples of self-actualization, which range from being a good parent to creating the artistic work one feels compelled to create.

How We Progress through the Hierarchy

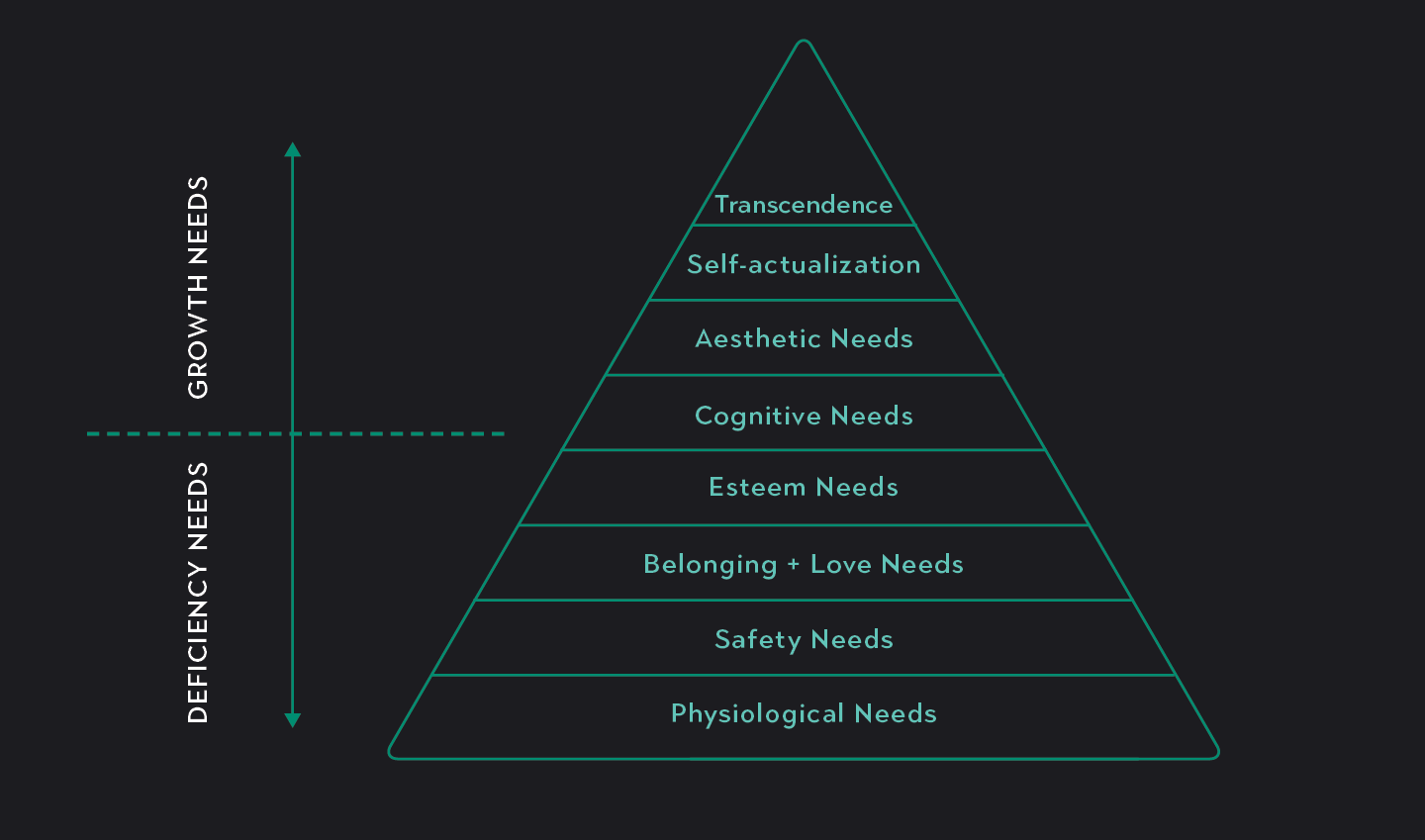

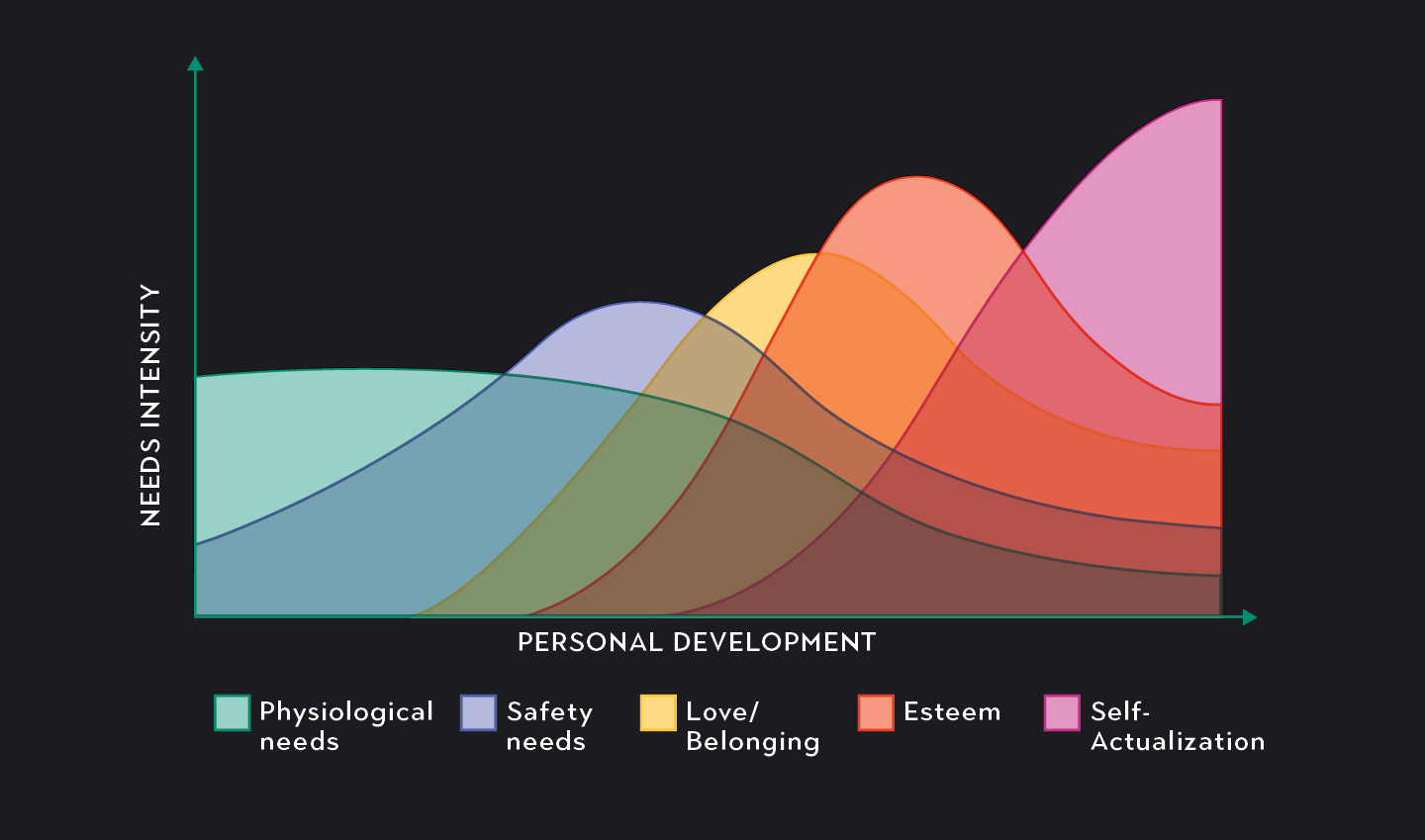

As one moves up the pyramid, not only do the needs change, but so too does the kind of motivation which drives one to fulfill these needs. Maslow identifies the first 4 stages as involving “deficiency” needs, while the 5th stage involves “growth” or “being” needs.

Deficiency needs are motivating when they aren’t met. They’re characterised by a feeling of anxiety or tension when unfulfilled, and the motivation to fulfill them only gets stronger the longer they’re not met. With deficiency needs, the motivation to pursue them comes from the negative effects that result from one not pursuing them. If, for example, you find yourself in a desert without a drop of water in sight, you’re only going to get thirstier until you can satisfy your body’s need for water.

In Maslow’s original hierarchy, only self-actualization was identified as a growth need. Growth needs are driven by the desire to develop. Unlike deficiency needs, as growth needs are met, the motivation to fulfill them actually becomes stronger. Imagine that you’re learning to play an instrument or speak a foreign language: maybe it’s frustrating at first, but as you continue to get better and better, the desire to refine and deepen your ability grows increasingly strong and your satisfaction with your achievements becomes increasingly profound.

The Expanded Hierarchy

In Maslow’s initial presentation of the hierarchy in Motivation and Personality, only self-actualization featured as a growth need. However, in later works, including later editions of Motivation and Personality, Maslow identified 3 other kinds of growth needs not captured by self-actualization.The first, cognitive needs, comes after esteem needs in the hierarchy and refers to the human need for creativity, predictability, curiosity, and meaning. In practical terms, this describes the human need to be able to understand and make sense of their environment, while also being able to come up with novel solutions to problems.

After cognitive needs come aesthetic needs. Though he acknowledges that this need is relatively opaque, Maslow nonetheless asserts that almost everyone feels some desire for satisfactions of an aesthetic sort. In his conception, this doesn’t entail lofty ideas about art or beauty (though it doesn’t rule them out either), but rather simple needs for structure, symmetry, or resolution. He sums it up in his typically concise manner: “What...does it mean when a man feels a strong conscious impulse to straighten the crookedly hung picture on the wall?”

The 8th and final stage in the expanded hierarchy, past self-actualization, is transcendence. Transcendence, as a need, describes the motivation to go beyond our personal self, whether by mystical, religious, aesthetic, ethical, and ideological pursuits. Core to all of these is that one’s motivation and goals relate to something bigger than oneself, whether that’s society at large, some group of people, or a higher power. As Maslow puts it in his The Farther Reaches of Human Nature (1971): "Transcendence refers to the very highest and most inclusive or holistic levels of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means, to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos."

Criticisms of Maslow's Hierarchy

As with any widely influential theory, there have been numerous criticisms of Maslow’s hierarchy over the years, but let’s consider just a few of the most important here.

Sampling Bias

Maslow’s methodology, particularly his use of biographical analysis, has been criticised for being unscientific and biased. His work was initially based on a mix of interviews and historical research regarding 18 individuals who were thought to be either “fairly sure” or “highly probable” instances of self-actualization, a group comprising both contemporaries of Maslow and a number of significant historical figures. (His findings were supplemented with considerations of several dozen further individuals whose self-actualization was less certain.) The goal was to find what was common between these individuals and absent in non-self-actualized people. The most basic issue with this approach is that Maslow selected the 18 people himself, meaning that the sample was likely to be biased toward what he hoped to find. It also must be noted that Maslow’s sample consisted largely of white men from Western backgrounds, a fact which raises significant doubts regarding its ability to identify common motivational features across all humanity.

The Ranking of Sex

Maslow placed sex in the physiological needs category, a fact which has been criticised as ignoring important aspects of sex, such as the emotional bonding component. His ranking has also been criticised on the grounds that sex is not, unlike air or food, a universal need.

The Rigidity of the Hierarchy

The lack of flexibility in Maslow’s model has also been criticised. It has been argued that the hierarchy is not universal and unchanging, but actually varies across cultures and according to different environmental and sociological situations. One recent study has shown that the needs of people in the Middle East and the US at the same time were completely different.

Louis Tay and Ed Diener carried out a large study of over 60,000 subjects across 120 countries and found that although needs similar to Maslow’s categories were important to people’s well-being, the order in which those needs were fulfilled was much less rigid. Tay and Diener conclude that the ordering hierarchy is far more fluid than Maslow had imagined. Diener claimed that the needs are more like vitamins: “we need them all.” Indeed, Maslow himself noted in the third and final edition of Motivation and Personality that his initial model was overly rigid.

Explore Outlier's Award-Winning For-Credit Courses

Outlier (from the co-founder of MasterClass) has brought together some of the world's best instructors, game designers, and filmmakers to create the future of online college.

Check out these related courses: